André Malraux said Haitians were a nation of poets. Lyrical and rebellious, Georges Castera was one of the characters and voices of the island. As he has just left this world, let’s go back and reflect on his work and destiny.

He left the way he lived, and where he lived: in Pétion-Ville, as a Haitian poet. For Haiti, losing Georges Castera means losing one of its greatest and most beautiful voices. His work is beyond time: rather than being mourned, he must be read. Victor Hugo once said that poets are eternal, as long as they are understood and heard.

Credit Photo : Shutterstock

Castera bore the gentle face of an intellectual, with a touch of jovial serenity that covered up his share of torment likely originating from his exile, a life away from Haiti, his true love. Fleeing dictatorship, he lived in New York in the 1970s. But exile turned out to be more an opportunity than a punishment. The young man would dream of literature and end up in the heart of the exiled Haitian community’s intellectual turmoil. He discovered jazz and theater. He was a regular at the Haitian Corner bookstore, which influenced his double-faced writing style, both in French and Creole. A bit of Spanish as well, but Castera will always be the prince of Haitian words, mixing registers, one pun after another, such as “catastrophe” which he turned into a verb, to affirm his melancholy. He wrote his first texts in 1974 and was immediately successful.

Growing up on the island, Castera learned a lesson. He was born in a bourgeois family in Pétion-Ville, one of the capital’s fancy districts, where his mother managed a hotel. His father was a doctor; however, Georges wanted to live among the most humble. From this gap between the rich and poor, Castera breathed fire and indignation. Illustrious Haitian writer Lyonel Trouillot wrote “When you are Georges Castera fils, you have to become a doctor like your father, especially after two years in France and eleven years in Spain. You don’t go through fifteen years in the United States as a worker and come back home with your pockets full of poems.” Yet his poetry was not social: It was a larger wound, encompassing all misfortunes and sorrows. French academician and famous Haitian writer Dany Laferrière compared him to novelist James Baldwin. They shared the drying up or thirst of exile. Ordeals of the heart and indignation towards the world. A taste for revolution and hatred of misery. But Castera remained a man, a poet, guided by a yearning for beauty.

Take his magnificent verses or his two most beautiful collections of poems: ” Rature d’un miroir – Ratures of a Mirror” or ” Les cinq lettres – The Five Letters”: “She comes, the sea / to wash her salt in our tears / she comes to recharge with salt / her foaming rage / with the same rhythm of the sea / the same rhythm of the land / deep, riddled with dead stars .” Castera a part of the most beautiful French poetic tradition. Nourished by revolt, and yet transcended by the world’s splendor. Something like Rimbaud’s escape and race to the stars.

When dictatorship ended, Castera returned to Haiti from New York. He then became the devoted friend of younger writers, a highly celebrated playwright, a well-admired writer. “Ink is my home”, one of his finest phrases and

also the title of his anthology, says it all. Exile and uprooting: his words, his pages as well as the two languages that lived in him wonderfully were his only home. And of course his vocation as a poet, which he never gave up until the end, even in his eighties. As Trouillot describes in the introduction to his anthology, “His poetry had no room for nostalgia, remaining faithful to rebellion and not to the past. Writing poetry (in Creole moreover, this language which in the 1950s was not yet recognized as such by erudite people or in sophisticated circles), taking it seriously as a life choice and the main link in his relationship with the world, was his greatest rebellion.”

You have to read Castera to understand Haiti, to hear the sounds of Port-au-Prince, its madness and its beauty. In his staccato language, everything starts to move and Haitian fever arises. His island celebrates him as a prodigal son. He planted flowers in the minds of younger Haitian poets that will long bear fruit.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

LES CINQ LETTRES (RÉÉDITION, MÉMOIRE D’ENCRIER, 2012)

HAÏTI PARMI LES VIVANTS, COLLECTIF (ACTES SUD, 2010)

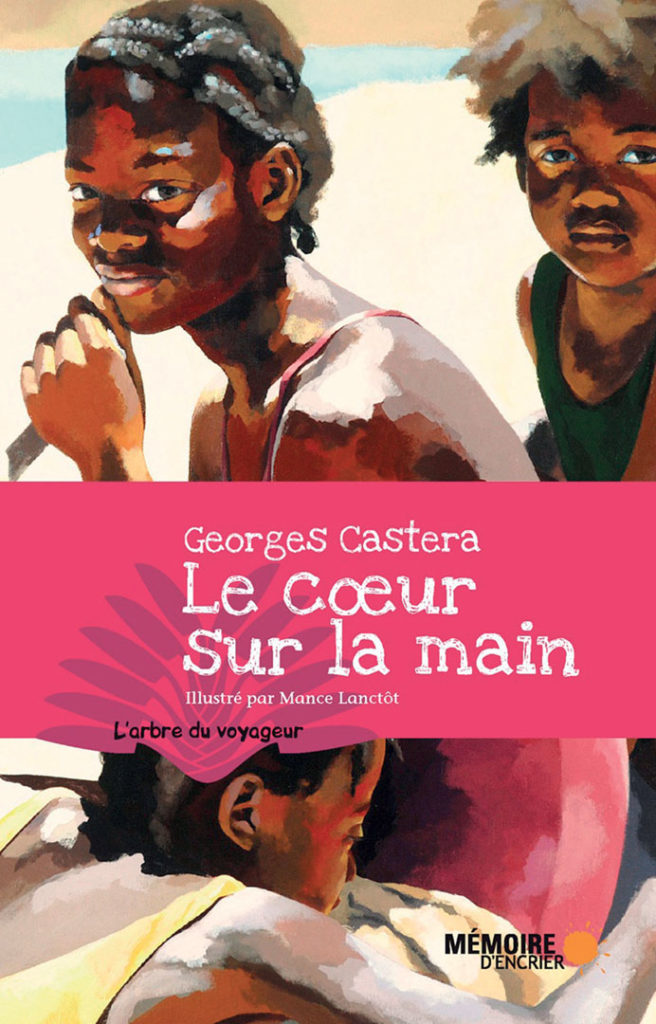

LE COEUR SUR LA MAIN, ILLUSTRATIONS MANCE LANCTÔT (MÉMOIRE D’ENCRIER, 2009) LE TROU DU SOUFFLEUR (CARACTÈRES, PARIS, 2006)

L’ENCRE EST MA DEMEURE (ACTES SUD, PARIS, 2006)

BRÛLER (PORT-AU-PRINCE : ÉDITIONS MÉMOIRE, 1999)

VOIX DE TÊTE (PORT-AU-PRINCE : ÉDITIONS MÉMOIRE, 1996)

QUASI PARLANDO (PORT-AU-PRINCE : IMPRIMERIE LE NATAL, 1993)

LES CINQ LETTRES (PORT-AU-PRINCE : IMPRIMERIE LE NATAL, 1992)

RATURES D’UN MIROIR (PORT-AU-PRINCE : IMPRIMERIE LE NATAL, 1992)

LE RETOUR À L’ARBRE, AVEC DES DESSINS DE BERNAH WAH (NEW YORK : CALFOU NOUVELLE ORIENTATION, 1974)